Incarnated Love | Works of Love, Addendum I

Why Love must be more than "A will for the good of the other".

In the process of writing my read-along article for chapter one of Kierkegaard's Works of Love, I stumbled across this passage:

But you should not for that reason hold back your words any more than you should hide visible emotion if it is genuine, because this can be the unloving committing of a wrong, just like withholding from someone what you owe him. Your friend, your beloved, your child, or whoever is an object of your love has a claim upon an expression of it also in words if it actually moves you inwardly. The emotion is not your possession but belongs to the other; the expression is your debt to him, since in the emotion you indeed belong to him who moves you and you become aware that you belong to him. [...] You should let the mouth speak out of the abundance of the heart; you should not be ashamed of your feelings and even less of honestly giving each one his due.1

This passage strikes me for a variety of reasons. As long-time readers will know, much of my time is devoted to thinking about friendships, family, and other non-romantic relationships. I've written about some of the problems I face as a single man, as well as some of the myths and untruths I commonly encounter about the term "church family". From this it may reasonably be inferred that I am thinking of this passage in dialogue with our current cultural views about friendship.

In particular, this paragraph rubs up against something we encounter when we consider the value of friendship. Friendship, especially for men, has gone from a deeply cherished, often lifelong commitment, to the group of acquaintances one has a beer with on Sundays at the bar while watching football on the TV. The sentence "she is a friend of mine" contains almost no true information, because "friend" can mean anything from "I've known her since I was three years old" to "I met her three hours ago at a party and we talked for five minutes." Friend, much like the word love, has no cultural weight.

In my experience, this is especially true for men. Men are often told to actively suppress their emotions, not bring them out. And while this is most true for negative emotions, the teaching extends to positive ones as well. If you are a man, do you hug your friends? Do you tell any of your friends that you love them? How uncomfortable does the thought of saying that make you?

I ask this not to make anyone feel bad, but to point out how impoverished our culture is when it comes to giving friendship its due. We are very far removed indeed from the times when Seneca could write the following:

What is my object in making a friend? To have someone to be able to die for, someone I may follow into exile, someone for whose life I may put myself up as security and pay the price as well. [...] There can be no doubt that the desire lovers have for each other is not so very different from friendship – you might say it was friendship gone mad. [...] Actual love in itself, heedless of all other considerations, inflames people’s hearts with a passion for the beautiful object, not without the hope, too, that the affection will be mutual. How then can the nobler stimulus of friendship be associated with any ignoble desire?2

We do not live in such a time. No, we live in a time where friendship is nothing more than a side dish—if that—in the great banquet of life. Daniel Kim, in the latest edition of Inkwell, writes that “Beauty is persuasive, seductive, violent, even! We don’t grasp it. It grasps us. Beauty captivates us, which means that it also takes us captive!” Are we even capable, as a culture, of having that reaction for a friend? What would it look like for us to become captivated, enraptured by our friends, as Seneca clearly was?

While it is particularly a struggle for men, it is not unique to men. Western culture has absurd standards for all involved, for what is and is not allowed or expected within friendships. One author speaks of writing a letter to a friend, declaring her undying affection for her friend in a birthday card. "I love you. I feel like I've known you for many lives, and I will know you for many lives to come." Yet this author reported feeling shame for "loving a friend too deeply", shame for her feelings, shame for giving her friend her due.3 She felt the shame so strongly that she did not give the card to this friend. How has our culture become such a wasteland of misunderstandings about the nature of love?

We should reject these standards all the more strongly because it is the predominant stance. We should use our words to declare openly the value of friendship. Beyond that, I think this passage speaks to an even broader principle, expanding beyond words: namely, that love is to be incarnated.

Incarnated Love

God's love was so strong that he took on mortal flesh for us, joining us in our suffering and dying for our lost cause, that it may not be lost any more. If a physical body is good enough for God, why do we so often treat our material bodies as immaterial, worthless trash, unable to aid us in our love of others?

What we do with our bodies matters. Speaking as a man here, my brain exploded eight ways to Sunday when I learned that my body is connected to my emotions. Wild, I know.4 So much of the church experience and frankly, experiences in general—are as Charles Taylor terms it, "excarnational"—highly intellectualized, overly cerebral, purely mental. When churches turn excarnational, the body becomes worthless, Christianity loses its embodiment, and it becomes nothing more than another belief system. I, at least, often have to consciously remind myself that I am not a brain floating in a vat who can just do whatever he thinks is "rational". No, I am a soul and a body, integrally connected together, which means that my body can tell me things about my experiences. I am an incarnational being, not an excarnational being.

The connections between my body and my emotions became apparent to me while processing difficult, negative experiences. A vague sense of tightness, a bit too much energy, a churning behind my stomach—these are signs that I'm nervous or anxious. But it was through paying attention to my body's reactions to various negative memories and emotions that I recognized the reverse is also true. There is a reversed experience, one wherein my body physically relaxes when I feel well emotionally. Conversely, taking concrete steps to help my body relax will have a correlated emotional component. And very often, there is a notable shift in my body and emotions whenever I receive simple things like hugs from beloved friends or family.

After all, is it really surprising that our bodies are part and parcel of how we experience love? I shouldn't be surprised that feeling loved requires honoring my physical, incarnate nature, yet I am. Our love should be incarnational, to match our incarnated nature. The Bible even speaks of this! It stares us right in the face; it is mentioned at the end of five different New Testament letters:

Romans 16:16: Greet one another with a holy kiss. All the churches of Christ greet you.

1 Corinthians 16:20: All the brothers send you greetings. Greet one another with a holy kiss.

2 Corinthians 13:12: Greet one another with a holy kiss.

1 Thessalonians 5:26: Greet all the brothers with a holy kiss.

1 Peter 5:14: Greet one another with the kiss of love. Peace to all of you who are in Christ.

So often, we dismiss these verses as impractical wisdom from a bygone culture. We do not stop to consider the deeper wisdom behind them. We no longer kiss people as a greeting, so what good does it do us?

This command should not be brushed away so brusquely. After all, how many other things are commanded to the audiences of five separate New Testament letters? If Paul and Peter saw fit to make explicit note of this, we would do well to pay attention. These commands are a window into the necessarily incarnated nature of human-to-human love. Love is not just some abstract feeling, some ineffable "willing the good of the other". No, love must be incarnated in and through the world. Once we note this principle, we see it elsewhere, such as in James:

James 2:15-16: If a brother or sister is poorly clothed and lacking in daily food, [16] and one of you says to them, “Go in peace, be warmed and filled,” without giving them the things needed for the body, what good is that? (ESV)

What good is that, indeed?

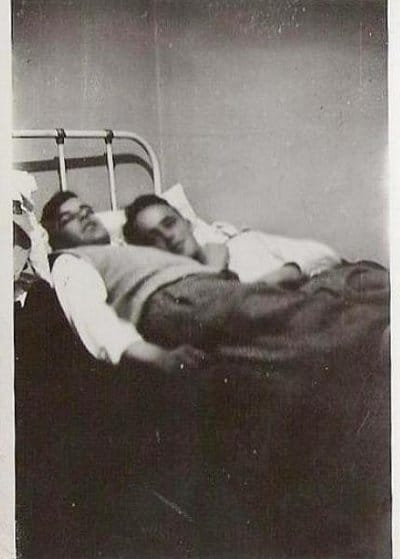

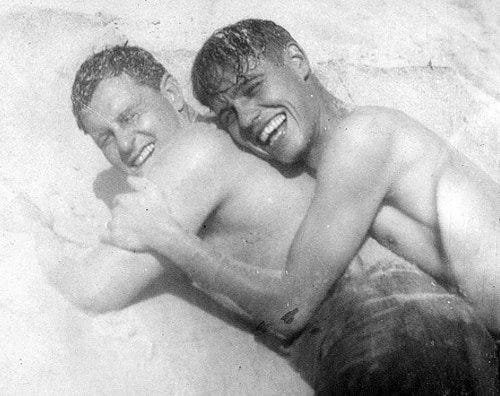

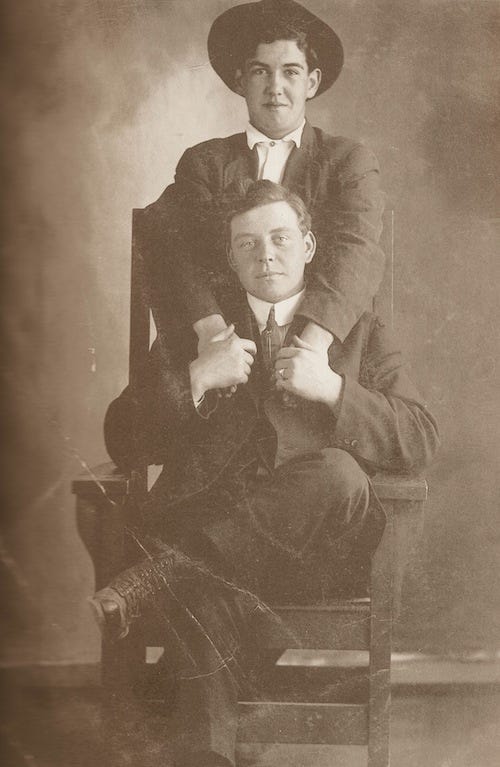

We are a remarkably disembodied culture. This is not universally true; there are still many cultures where a much healthier respect for our existence as embodied beings exists. Physical touch between friends is the norm, not the exception, in places like Korea.5 This was even true in America not that long ago.6 Here’s just a couple photos from 19th century America depicting normal friendly affection:

(The whole article, linked in footnote 6, is worth a scroll-through.) But at least where I grew up in America, two male friends holding hands is a radical departure from the norms, which comes with more than a bit of suspicion from those around you. Perhaps, as O. Alan Noble writes in an excellent recent article, the church needs to practice the Holy Hug.

Now, it is also important to note that part of relearning the incarnational nature of love is allowing for nuance. Bodies have histories, too. Some of my friends are touch-averse because of childhood sexual abuse—any attempt to force a hug on them would be failing to love their incarnated, embodied history. Part of recognizing our embodiment is recognizing that it is messy and complicated.

Nonetheless, I think we err far too strongly on the side of viewing our existences as a disembodied, spiritual phenomenon. Part of rectifying this is honoring our incarnated nature in our practices of love. If the ultimate act of love is God becoming Incarnate and joining us in our embodied suffering, then we would do well to incarnate our loves in our own ways. Just as SK reprimands us for not recognizing that our "emotion is not your possession but belongs to the other;"7 so also we should recognize that love must be expressed with physical action.

My encouragement, for Christians and non-Christians alike, is to be more forthcoming with your love. Hug a friend, tell a parent you love them, do something today to honor your debt to those who you love. For, as Kierkegaard tells us, "you should not be ashamed of your feelings and even less of honestly giving each one his due."

Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, p. 12. For details on what edition I am using, see my Part 0 post for the read-along here.

Seneca, Letter IX.

The author in question is Marisa G. Franco, who wrote a book, Platonic, that I plan to read eventually. Her talk where she talks about this experience with the letter can be found here:

Based on my purely anecdotal experience when talking about this amongst friends, all of the women reading this are going "You didn't know that already?" and somewhere around half of the men are wondering if this thing about emotions and the body could possibly be true. To the men: it is true.

See, for example, this article by Bridget Eileen Rivera, where she writes “Teenage boys talking about how they “slept together” last night, meaning that they decided to share the same bed and nothing more. Even my own good friend in South Korea held my hand or put her arm around my waist whenever we got together. To the average Korean local, we looked completely normal. But to the average American, we’d look romantic.”

https://www.artofmanliness.com/people/relationships/bosom-buddies-a-photo-history-of-male-affection/

Works of Love, p. 12.

The Seneca quote reflects a world still bound by the patron-client system. Friendship was a virtue in those days because politics and society were intensely personal. Everyone counted on their friends to protect their property and interests.

The rise of print began the long decline of friendship. Print enabled the symbolic construction of vast bureaucracies. These bureaucracies, animated by abstractions like “The Nation,” became the mediator between individuals.

As we have become more efficient at mass producing symbols, we have likewise become more efficient at siloing individuals into their own private cells. Individual relations are so deeply mediated by impersonal institutions that genuine friendship is extremely difficult to achieve.

I think you're expressing something very real. Print culture and industrialization certainly have something do with it, but we shouldn't ignore the obvious factor of gender roles and gender expression. I've been reading around in Melville recently so Ishmael and Queequeg are on my mind. Their friendship is called a marriage multiple times and includes a lot of touch and physical intimacy. The chapter "The Monkey Rope" is an extended reflection on our bonds in society and how we are simultaneously (due to scale and global capitalism) forced to interact with each other as members of a massive joint-stock company but also never without the dependency, acknowledged or otherwise on people in our lives, even those who don't know us. MacIntyre reflects constantly on community, tradition, and friendship, and how those goods are threatened not by "modernity" in general, but the social forms of capitalism in particular. But I don't think there is some silver bullet explanation and there are always a variety of mid-range and particular factors. Part of why literature is so essential! I've always found D.H. Lawrence particularly attentive to the loss of the tactile (in eroticism, but also in lived experience generally). Loving the Kierkegaardian insight that you are obligated to express your emotion.