Knowledge and the Body

Reflections on The Intellectual Life I

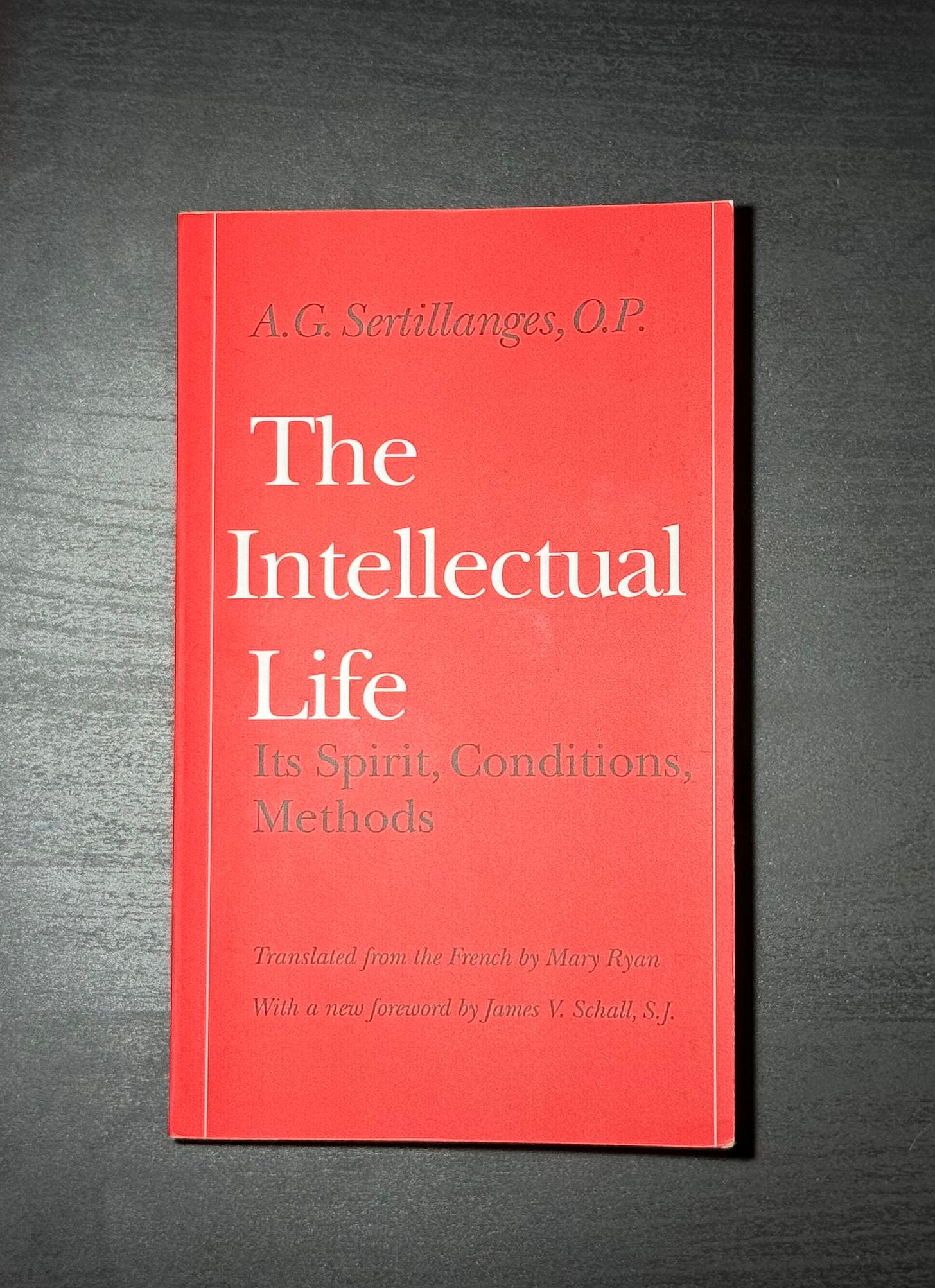

For the past few weeks, I've been reading through A.G. Sertillanges' wonderful book The Intellectual Life for the third time. It's a yearly reread for me, as it always invigorates my desire to read, learn, and grow.

One passage in particular stood out to me this time through in a way that it hasn't before:1

When we want to awaken a thought in anyone, what are the means at our disposal? One only, to produce in him by word and sign states of sensibility and of imagination, emotion, and memory in which he will discover our idea and make it his own. Minds can only communicate through the body. Similarly, the mind of each one of us can only communicate with truth and with itself through the body. So much so, that the change by which we pass from ignorance to knowledge must be attributed, according to St. Thomas, directly to the body and only accidentally to the intellectual part of us.

This struck me because I am thinking and reading about the theology of the body. What do our bodies mean? How should we relate to them? These questions include sexuality, as you may have deduced by my previous articles,2 but are not limited to it.

I haven't read the part of Aquinas that he's referencing, nor could I give extensive philosophical arguments for why it is the body that is essential in knowledge, but nonetheless, it appears right. It is our bodies that mediate the transfer of knowledge, not our intellects.

Our culture has gotten this exactly backwards. I've noticed that in my own conception of self, my body is just something that I have. It's accidental. I can easily separate my "self" from my body. Yet this seems wrong on inspection: I don't just have a body, I am a body. My fingers, my back, my legs are all an intrinsic part of who I am; if my body stops working, I lose my ability to learn. And even when someone has an arm amputated, we all recognize that they've lost a part of themselves. Yet we don't extend this line of thought to our everyday self-conception—or at least, I don't. The body is not given its due.3

I can't help but wonder if this failure to recognize the importance of the body is part of why friendship is valueless in our society. If indeed our bodies are the central locus of learning, how does one signal love to another? Indeed, one may signal it through the spoken word, through time spent together, through gifts—yet we do not consider physical touch in friendship. The body is not given its due.

Many of my newer friends are surprised the first time I ask for a hug as a hello or a goodbye. Culturally, this is because we associate functionally all forms of physical touch with romance and/or sex, which are out of the bounds of friendship for most people. This is absurd, of course. There is nothing sexual or romantic about greeting my parents and grandparents with hugs. If indeed the body is integral to our capacity to learn, do we not need to experience friendship physically?

At least in my experience, some of the most powerful expressions of love are simple physical acts. Even in writing these words, I can feel the desire to clarify that this does not mean they are sexual acts. This is a clear sign of how far our culture has taken physical touch into the exclusive realm of the romantic. A hug from my parents when I come home; the strong, rough embrace of a close friend after a long absence of presence; a roommate holding my hand at 2am during a rough night. All of these things make the love real, something tangible in the world, something physical, something that my body recognizes and says "this is good". It solidifies the love into something that is just a little bit harder to refuse when my brain turns on me, because my body knows there is love to be found even when my intellect rejects it. In other words, I come to learn that people love me through the body.

From all this, it seems possible to me that part of why friendship is so undervalued is because there is no longer a physical aspect to friendship love, to philia. If the body is how we come to know all things, perhaps we must also come to know our friends love us through the body. Perhaps learning love bodily ought not be restricted to romance.

None of this has been particularly rigorous. I would love to hear the thoughts of others on this, so please leave a comment down below if you have any thoughts, agreements, disagreements, soliloquies, or theses to hammer to a doorway.

The below quote is from A. G. Sertillanges, The Intellectual Life, p. 34-35, citing Aquinas, Q.XXVI De Veritate, art. 3, ad 12m.

As a Christian, the question of how the resurrection will work metaphysically is an interesting one. However, I am wholly unqualified to discuss that particular thorn, here or anywhere.

Something interesting is that Christ actually made a lot of physical contact with the disciples or people he healed. Take John 13:23, for example. A disciple is cuddled up to Him, just chilling. (For some reason, newer translations say the disciple is "reclining next to" Jesus, but KJV clearly says the disciple was "leaning on Jesus' bosom.") And while, yes, this is a Creator and child bond, it's also a casual, familiar embrace between two friends. (Let's also not forget kissing was a normal thing between friends back then coughJudascough.)

It's sad we've become so disconnected from each other. I shouldn't get nervous to simply lay a hand on someone's shoulder.

I think you're right, although ofc there's the perrenial chicken and the egg question. I expect part of the reason friendship has become less physical is because of a fear that'd the physicality would be seen as sexual. Thus we need to understand our changed view of sexuality and physicality itself that may have contributed to this, and where the worry the physicality indicates sexuality (or at least a risk of) comes from in our culture. I simply don't know enough about this to make any such claim. I can imagine that in victorian times or the like it was not seen as appropriate for a man and a woman to touch eachother in such a way (though I'd actually have no idea, this could easily be some anachronism from our received cultural narratives about the past). If this is the case it may then just be that such sexual codes have simply been expanded. I do expect though that irregardless of historical claims, I think part of the reason why our friendships are less physical now is out of a fear of tthere being something sexual in that. That's part of the reason that our physicalities are largely restricted to family or maybe someone who there's seen to be no risk of anything sexual (like in my case some of the older women at church who serve a sort of mother figure role).

I think you're broadly right though that the view of friendship as two people looking forward together at the same thing rather than looking at eachother like (romantic) lovers do (as CS Lewis describes it in the four loves) goes hand in hand with the decreased physicality of friendships. We know from previous centuries that close emotionally intimate friendships were alot more common than they are now. Once again there's the ultimate question of the chicken and the egg. I guess though more important than that is how do we change that, how do we provide space for more physicality and more intimacy in friendhsips, which I also don't really know how to answer.