Love's Blessed Independence | Works of Love, Chapter IIa (Part V)

Reading Kierkegaard within the mystic tradition

Matthew 22:39: But the second commandment is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself.

Today we continue our read-along of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love. If you haven’t read them yet and want to catch up, here are links to the first and most recent articles on this chapter:

As we saw in part III, Kierkegaard presented us with a sort of summary for what the rest of the chapter will explore:

Only when it is a duty to love, only then is love eternally secured against every change, eternally made free in blessed independence, eternally and happily secured against despair.

In part III, we focused on love becoming “eternally secured” by love becoming duty. Last time, in part IV, we focused on the two ways love can be changed—love can be changed within itself and for itself. We also saw how love, when it becomes duty, is secured against those changes. This week, we turn to seeing how love is “eternally made free in blessed independence.”

Kierkegaard showed us last time that love, for it to remain true love, must retain “its ardor, its joy, its desire, its originality, its freshness.” (p. 36) If we truly want to keep love—and anyone who has experienced love knows that love is worth keeping, indeed is the gift worth keeping above every other gift—then we must not allow it to fall into disrepair. We cannot become habituated to the glory of another person; no, we must continue seeing the face of God through them.

This leads us to a trap, however. It is alluringly easy to ground one’s love in receiving particular things, especially those which upbuild love’s ardor, joy, and freshness. We say in our hearts, “I will continue loving you—as long as you remain beautiful to me.” This is perhaps the most assiduous, asinine aspect of all that comes from the gamification of romance. Humanity like never before has access to millions of other people on Tinder and Hinge, whom they can choose to swipe left or right on based on a few photos and a meager sentence or two. What is meant to foster love often begins with the highest form of selfish preference.1

This form of love-as-exchange is obviously banal, but there are more secretive forms of it, too. Many well-meaning people would say that they experience a need for the love of the beloved, or of a friend—and thereby say that they will only continue loving the friend or the beloved if they receive that love. This, too, grounds the reality of their love on receiving something from that other.

Kierkegaard, at first, seems to say to us that this basis of “love-for-love” is real and good:

On the contrary, we have pointed out above that the expression of the greatest riches is to have a need; therefore, that it is a need in the free person is indeed the true expression of freedom. The one in whom love is a need certainly feels free in his love, and the very one who feels totally dependent, so that he would lose everything by losing the beloved, that very one is independent. (p. 38)

And indeed, SK tells us back in chapter one that need, to have a need, signifies both “the utmost misery” and “the greatest riches” (p. 10). To need love, to need companionship is central to human nature—we will explore this in more detail in Chapter IV. It appears so far that SK praises needing another person. But we must be careful, for the ethical reality follows immediately behind, and we cannot escape love’s shall:

[...] that very one is independent. Yet on one condition, that he does not confuse love with possessing the beloved. If someone were to say “Either love or die” and thereby mean that a life without loving is not worth living, we would completely agree. But if by the first he understood possessing the beloved and thus meant either to possess the beloved or die, either win this friend or die, then we must say that such a misconceived love is dependent. As soon as love, in its relation to its object, does not in that relation relate itself just as much to itself, although it still is entirely dependent, it is dependent in a false sense, it has the law of its existence outside itself and is dependent in a corruptible, in an earthly, in a temporal sense. (p. 38, bold my own)

If love is as valuable as we all take it to be, then we must protect it from being corruptible, right? What Kierkegaard wants us to recognize is that any impulse which says “if you cease to love me, then I shall cease to love you” makes love dependent—on someone or something else, on an external reality. But love which takes eternity’s shall into itself, that love depends only on this shall and is therefore eternally secured; it is dependent on an internal reality. “Spontaneous love makes a person free and at the next moment dependent. [...] Duty, however, makes a person dependent and at the same moment eternally independent.” (p. 38) When we love spontaneously (and when this is taken to the extreme), we are free to love based on our preferences, but that love immediately becomes dependent upon those preferences being fulfilled. When we love according to this shall, love is dependent on this command, but then eternally free from any external conditions taking away our love.

We might expect (or at least I did), based on this shall, that the person who takes eternity’s command into his love no longer experiences the need for reciprocal love, the need for the other. What I find so fascinating in Kierkegaard’s account here is that he follows up this security of love through the shall by noting precisely the opposite—that the loving one still has need for the other person!

Sometimes the world praises the proud independence that thinks it has no need to feel loved, even thought it also thinks it “needs other people—not in order to be loved by them but in order to love them, in order to have someone to love.” How false this independence is! It feels no need to be loved and yet needs someone to love; therefore it needs another person—in order to gratify its proud self-esteem. [...] But the love that has undergone the change of eternity by becoming duty certainly feels a need to be loved, and therefore this need is eternally in harmonizing agreement with this shall; but it can to without, if so it shall be, while it still continues to love—is this not independence? (p. 39, italics original, bold my own)

In other words, for Kierkegaard it is not only good but necessary for love to desire being loved—yet in such a way that receiving love does not change my own love for the other person. In this way my love gains stability, it becomes independent.

Kierkegaard, a mystic?

I mentioned last time that Theodor Adorno and those who have followed him have, in my view, failed to understand Kierkegaard’s view of love. As I’ve meditated on the reading in this section, I have become more certain that Adorno is wrong, and I believe it is worth unpacking more of exactly where he misses the point. This is in service of a new thesis that I am gradually coming around to: Kierkegaard was a mystic—or at least, profoundly mystical.2 We will only begin to sketch this thesis here. I plan to gradually build it up (or tear it down, if need be) as we go along.

Adorno addresses our book most explicitly in his article fittingly entitled On Kierkegaard’s Doctrine of Love.3 After insulting Kierkegaard’s religious writing as “continually repeating itself,” threatening the reader with “loquacious boredom”,4 Adorno summarizes Works of Love as follows:

In Kierkegaard’s doctrine the “Christian” content of love, its justification in eternity, is determined only by the subjective qualities of the loving one, such as disinterestedness, unlimited confidence, unobtrusiveness, mercifulness, even if one is helpless oneself, self-denial and fidelity. In Kierkegaard’s doctrine of love, the individual is important only with respect to the universal human. But the universal consists in the very fact of individualization. Hence love can grasp the universal only in love for the individual, but without yielding to the differences between individuals. In other words, the loving one is supposed to love the individual particularities of each man, but regardless of the differences between men. [...] Kierkegaard’s love is a breaking down of nature, moreover, as a breaking down of any individual interest of the lover, however sublimated it may be. The idea of happiness is kept aloof from this love as its worst disfigurement. Kierkegaard even speaks of the happiness of eternity in such gloomy tones that it appears to consist of nothing but the giving away of any real claim to happiness. (Adorno, p. 415-416, bold my own)

One would be forgiven for questioning at times whether Adorno knew how to read. The most egregious example occurs a page later:

Perhaps one may most accurately summarize Kierkegaard’s doctrine of love by saying that he demands that love behave towards all men as if they were dead. (Adorno, p. 416-417)

Perhaps it is just me, but when I read that it is my duty to continue loving the neighbor with all ardor, desire, freshness, originality, and joy (p. 37), I don’t get the sense that SK demands I treat those in my life as if they were dead. Of course, Adorno is responding to the work as a whole, and this quip is a reference to Chapter IX of the second series, entitled The Work of Love in Recollecting One who is Dead. We will get there in time, dear reader; what remains is that Adorno fails to see just how invigorating and life-giving Kierkegaard views love as. Perhaps as a consequence of Adorno only having access to German translations of questionable quality; perhaps as a consequence of Kierkegaard being somewhat unknown even in Adorno’s time; nonetheless Adorno completely misses the mark when he says that SK speaks of happiness in gloomy tones.

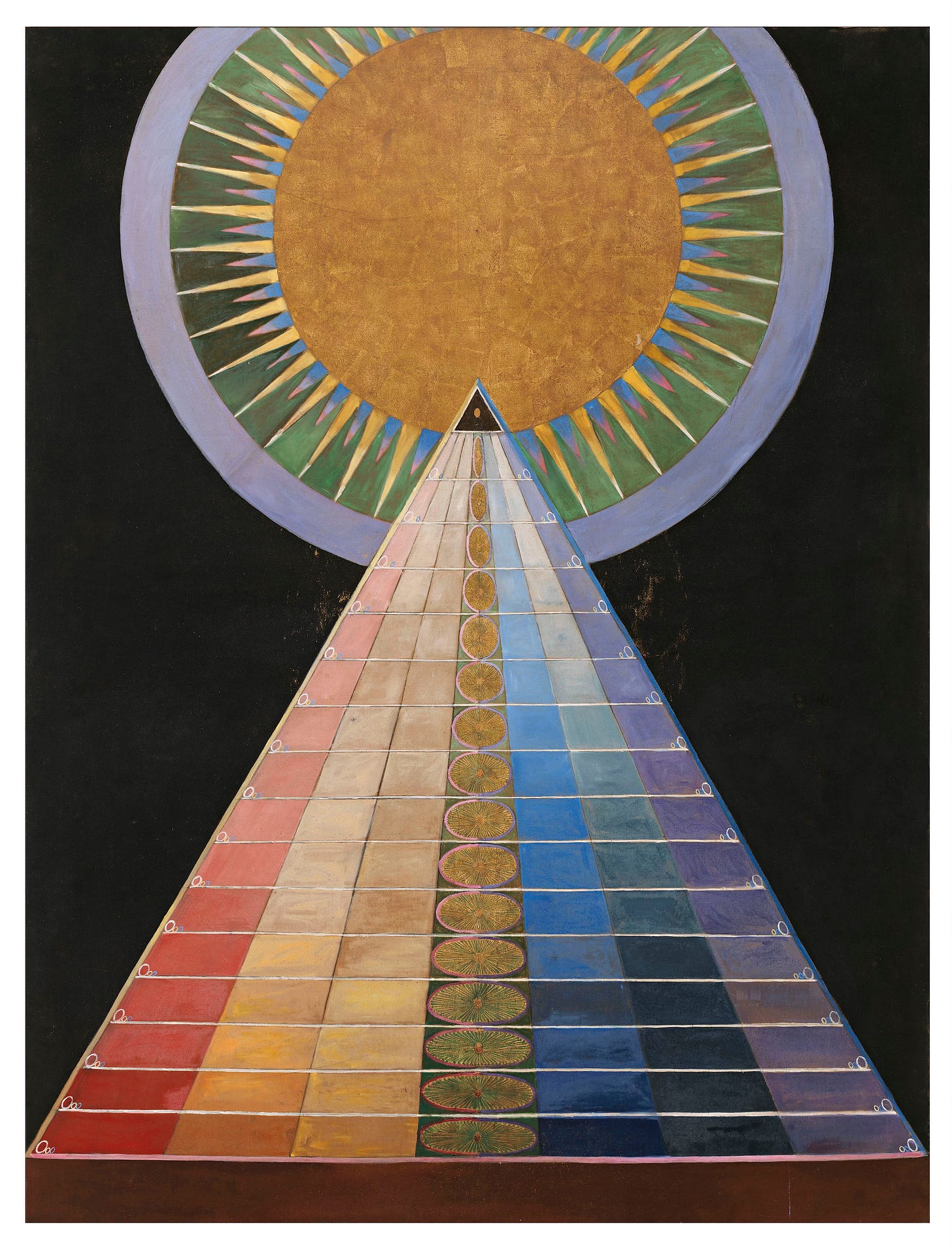

We must fight with all our strength against the forces of habit, which threaten to take away love’s ardor, freshness, and joy—is this the gloomy tone of one who believes we should love all men as if dead? Au contraire, part of remaining within love’s duty is sustaining our own need for the other person, for the love of the other person. We are not forbidden from desiring communion with persons—rather, we are to desire that person and their love, while simultaneously recognizing that our duty to love springs from God himself, not from any finite expression of love we receive. With these two things in mind, we begin to see the mystical vision that undergirds much of Kierkegaard’s thought. Consider these three passages:

Love’s hidden life is in the innermost being, unfathomable, and then in turn is in an unfathomable connectedness with all existence. Just as the quiet lake originates deep down in hidden springs no eye has seen, so also does a person’s love originate even more deeply in God’s love.

God is closer to us than our own soul, for he is the foundation on which our soul stands... For our soul sits in God in true rest, and our soul stands in God in sure strength, and our soul is naturally rooted in endless love.

God is in man, and in God is all. And he who loves thus loves all...

The first is, of course from Works of Love (p. 9). The latter two are from Julian of Norwich’s Showings. There is further resonance with the idea that God is closer to us than our own souls found in Kierkegaard’s The Sickness Unto Death, where the fully actualized self is seen to rest transparently in that which grounds it (i.e., in God’s love). This unity of self and the world through love is a common enough theme in mystical traditions of all kinds—I can only remain surprised that so few have noticed it running through Kierkegaard’s thought as well.

If our love originates in God’s love, and love also must retain its joy and desire and freshness—is there not in this something of the divine madness found in the Phaedrus?

Thus far I have been speaking of the fourth and last kind of madness, which is imputed to him who, when he sees the beauty of earth, is transported with the recollection of the true beauty; he would like to fly away, but he cannot; he is like a bird fluttering and looking upward and careless of the world below; and he is therefore thought to be mad.

Every interaction with love, with beauty, with life itself causes us to fly upward out of ourselves and plunge inward beneath ourselves to the source of all that is Good and True and Beautiful—God. We should not be so shocked to see Kierkegaard as a mystic, either. He was raised within the Lutheran Pietistic tradition, which has its own strain of mystic thought through Jacob Boehme, and he was intimately familiar with the thought of Franz von Baader as well. Indeed in several places, Kierkegaard presupposes that his readership is familiar with Baader’s writing. All this makes me wonder why so many readers of SK have been reticent to read him as a mystic alongside his ethical rigor. (If you want to explore more of the Lutheran mystical tradition, Ben Ames-McCrimmon has done some wonderful writing on the topic, e.g., this article.)

As usual for this series, we will pick up next time where we left off, which is:

Only when it is a duty to love, only then is love eternally and happily secured against despair. (p. 40)

If you have any thoughts, I would enjoy reading them down below in the comments. I would love to know what you guys think of this mystical reading which I am hastily sketching at—is it strained, is it reasonable? And as always, thanks for reading.

This is not to say that dating apps are universally bad—on the contrary, they do have positive, if limited, value when used correctly, especially for marginalized groups. But all too often the apps encourage a sort of aesthetic seeking of newness over real relationship.

Worry not—I will expound on exactly what I mean as we go.

Adorno, Theodor W., 1939, “On Kierkegaard’s Doctrine of Love”, Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, 8(3): 413–429. Thanks to the work of the Critical Theory Working Group there is a freely available pdf copy of this paper, which may be found at this link: https://ctwgwebsite.github.io/assets/pdf/zfs/adorno-kierk-love.pdf.

Adorno, p. 414-415

Thank you for the shout-out at the end. 🙂 It is really intriguing what you’re proposing — the ecstatic and world-affirming mysticism seem to come together here in Kierkegaard in a really interesting way. As you’ve said — this ecstatic moment goes back to Plato (and probably earlier — Anaxagoras? Pythagoras? Adam?) — but what’s interesting is that it has always been a feature of Lutheran theology — what they sometimes call the “extra nos” or the outside of self, where we are brought “into” another — in Luther, this is the role of Faith (see Freedom of the Christian), and Volker Leppin, for example, has located it as originating in how Tauler and the TD communicate to Luther Rheinish Mysticism. Obviously this ecstatic moment is important to Weigel and Boehme as well — in such a way that that which drives us out of ourselves in ecstasy is the very Will and love of God, attracted to us by our own repentance (self-emptying, Gelassenheit, etc.). So — deep wells.

Also, I would love to follow the Von Baader train a little more — he was obviously familiar with this tradition in a fundamental way. As was Schelling. Though they could drink more fundamentally from Plato and others due to the Neoplatonic revival going on at the time (see Naomi Fisher’s great book on the topic, “Schelling’s Mystical Platonism”). 🙂

This is a solid, accessible reading of Kierkegaard's view on love and dependency combined with the very interesting proposal that Kierkegaard fits within the mystic tradition. I admit I am not very familiar with mysticism, but I've discovered now that there is a lutheran mystic tradition and that excites me.

The mystic resonance with the anatomy of the soul in The Sickness Unto Death is particularly noteworthy, I think.

"All this makes me wonder why so many readers of SK have been reticent to read him as a mystic alongside his ethical rigor." I have an essay that addresses precisely this problem of "misreading" or "limiting" Kierkegaard that I've been working on for a long time and is nearing completion. There is so much to mine from his work!

I generally agree with your dispute with Adorno, however I am tempted to push back on your claim that Adorno stating Kierkegaard "demands that love behave towards all men as if they were dead" is a particularly egregious misreading. I don't yet have the context for this quote from Adorno, but I could see Kierkegaard having some fun with this statement: I am reminded of the excerpt in Works of Love where Kierkegaard says something like Shakespeare's "all the world's a stage, and we are mere actors," and then continues on: "the king, the beggar, the jester, when the show is done and the curtain falls, go backstage and remove their costumes and are all one and the same: actors." I think Kierkegaard sees death as a sort of unifying event. I think it is too far to say that he believes we are actually stripped of our individuality at death, but that in death we are all equals, and this should inform how we love our neighbor. The lutheran in me similarly finds something fun to play with in Adorno's statement: yes, we are to love all as if they are dead, for that is precisely what they are, dead in sin! It is only in the love of Christ, worked into them by their neighbors who love them, that they are resurrected also and clothed in the righteousness (and life!) of Christ. I doubt Adorno was making the statement with any of this in mind, but I think it's always fun to see how something that appears incongruent can be folded in. Again, I lack the context surrounding that quote, so this might be moot if the surrounding passages completely eviscerate what I'm saying!

I am looking forward to the next essay!