A lot of my friends give me a hard time because I typically don't listen to music written by anyone who hasn't been dead for a few decades. (I do listen, on occasion, to more modern music, but that's a story for another time.) Unsurprisingly, being the math nerd that I am, I love classical music. I've loved it for as long as I can remember, and while my tastes are broadening somewhat, I still listen to far more classical music than any other genre.

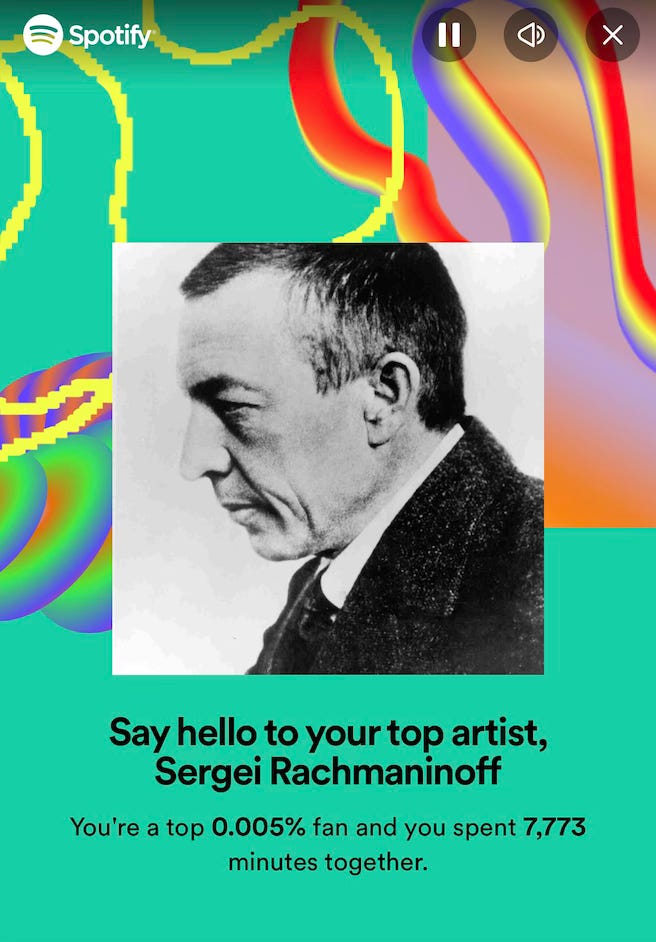

For anyone curious, this means I would rank somewhere in the top 150 in the world on Spotify when it comes to time listened to Rachmaninoff last year. I am a normal human person with normal musical habits. Much of my listening habits were formed by one critical thing: I've played piano since I was four. As such, whether consciously or not, when I listen to music, I am listening to it as a musician. I cannot hear music any other way. This fact drives many of my friends to consternation and despair, because I simply cannot stand to listen to a lot of the slop they call "music". My distaste for it is immense. I'll let Rick Beato's excellent video explain a bit of why this is the case:

This does not mean, of course, that all modern musicians are bad; I have found many bands, composers, etc., who absolutely pour their very hearts and souls into their musical craftsmanship. The fact remains, though, that I generally find the most musical mastery in the great composers of old. So today, I want to explain a little bit of why this is the case, and we'll do this by diving into two of my favorite composers: Bach and Rachmaninoff.

Storytelling and Craftsmanship

Before we can get to those two, though, we need to talk about two axes that will be useful as a scaffold for the discussion. When I'm listening to music, there are really two major things that I'm paying attention to, which I'm going to call "Storytelling" and "Craftsmanship". These words are not meant to be taken as definitions, nor are they mutually exclusive; rather they have the right feel for what I'm getting at with them, because it is not extremely rigorous. This is about vibes, not PhD-level analysis.

I am using "Storytelling" here to talk about what a piece of music is expressing. Music is most often conceived of as a way of telling stories, of communication, of narrative. This is most clear in pieces with lyrics, but one need not use words to tell stories. So, the kinds of questions relating to "Storytelling" here are things like:

Does this piece capture a specific emotion?

Does it bring out a certain time/place/memory in my mind when I hear it?

Does it have a plot? If so, is it told well?1

These things are, of course, extremely subjective. I make no claim to the contrary. The emotions that a piece may bring out in two different people are going to be potentially very different based on their own backgrounds, their own histories, their own narratives. That being said, I think there are certain composers that are incredibly emotive and expressive, doing so more, and more consistently, than many of their peers. One of these, for me, is Rachmaninoff.

Rachmaninoff

Born into an aristocratic family in Russia in the 1870s, Sergei Rachmaninoff did not have the easy life some would imagine him having because of his status. He went through a long bout of depression during his teenage years and early 20s, had to move permanently out of Russia because of political turmoil, and eventually died in America at the age of 69. Much of his work expresses the darkness he experienced throughout his life, in greater or lesser doses. His style is also characterized by a profound sense of melody; very rarely does Rachmaninoff not have a line he desires to be played "on top of" everything else.

Even if a composer has an image in mind, it is not particularly common for that image to be revealed. We do, however, know a couple of the images Rachmaninoff was attempting to impress onto the canvas of the ears in his Etudes Tableaux, meaning "study-images" – a set of works for solo piano – because of a letter he wrote to another composer who wanted to orchestrate them. In this letter, Rachmaninoff entitled the Etude No. 2 from the Opus 392 set as "The sea and the seagulls".

Before I analyze it, you have to go listen to this piece.

Have you done it? No? I'm serious – go listen to it. Don't read further until you've listened to this piece.

Alright. The piece opens with rolling waves of broken chords in the left hand. To the unsuspecting listener, this may sound like just another jumble of notes on the piano. Not so, dear reader! Before the melody has even come in, we have to talk about an aspect of the music that is more "Craftsmanship" than "Storytelling". (Again, these are not mutually exclusive; they often feed off each other, as they do here.) Rachmaninoff is doing something very interesting here, that should affect the way you hear the piece.

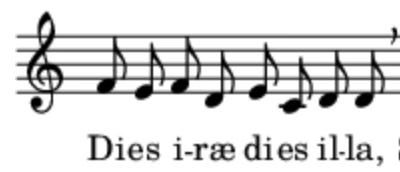

The first note of the left hand triplets (groups of three) are playing out the Dies Irae. What's the Dies Irae, you might ask? It's a very old plainchant poem that has played a part in the Roman Catholic liturgy for centuries. We have records of it going back to at least the 13th century, and in all likelihood it is even older than that. While Dies Irae means "Day of Wrath", when used musically like this, it's really a referral to the larger setting the Dies Irae functions in - the Requiem Mass, or the Mass for the Dead.

An excellent recording of the plainchant can be found here. Rachmaninoff here is citing it in a slightly abbreviated form; he takes the first four notes of the Dies Irae and uses them as a substratum from which to build the entire rest of the piece. To the listener who has ears to hear, let him hear, says Rachmaninoff - this piece is not a particularly happy one.

Knowing this detail, of course, does not solidify what a piece must mean to you, the listener. (Solidification comes when you write, after all; not when you read!) But it can – and, I would argue, should, now that you know it – affect how you hear it without railroading you into a specific feeling. This is, to me, an example of craftsmanship and storytelling meeting; Rachmaninoff is using craftsmanship, technical prowess, to weave the Dies Irae into the piece. Weaving in the Dies Irae serves the artistic, emotional function of tolling like a bell tower in the distance that this piece has a somber tone.

Having now explained some of the depth of what's going on in the first eight seconds of the piece, we may now proceed. The melody in the right hand floats above the waves, small and distant. What do the seagulls see? The waves, incessantly lapping against the shore, with the force of constancy, stability, because the ocean has always been and will always be.

The piece travels through several different key changes, shifts in tone; a sudden change to C# minor, seemingly from the depths, further hints at what is to come. I could go on – understanding the craft here could well take days of study (which I have not undertaken, by any stretch) – but I think my point has been proven. I will leave it to you to fill in the rest of the story yourself. In fact, Rachmaninoff supposedly said as much:

I do not believe in the artist disclosing too much of his images. Let them paint for themselves what it most suggests.

But the fact that there is a story to be filled in, that this piece will inevitably evoke a story to you, speaks of its power. And the story, the picture, though it is the focus, is not told at the loss of craft. This is an expertly put-together piece.

Bach

Who else could I speak of as my exemplar of the craft of music except Bach? Many people believe Bach plays a role, musically, that is similar to what Plato plays in philosophy: "All of philosophy is but a series of footnotes to Plato." Much as this deeply oversimplifies the depth of philosophical inquiry, many such quotes about Bach overstate the case. One such example is the famous quote of Douglas Adams:

“Beethoven tells you what it's like to be Beethoven and Mozart tells you what it's like to be human. Bach tells you what it's like to be the universe.”

It claims too much, of course: Bach is capable of being deeply Personal; Beethoven is capable of making oneself feel but a speck in the universe; Mozart captures more than just the fundamentally Human. But it is getting at something important, nonetheless. Bach placed an immense amount of value on the craft of the music. Some of Bach's music, for me, does not express one particular emotion; occasionally I'm not sure if I could even begin to talk about emotion in Bach. And yet it remains some of my favorite music to ever be written, because of the level of craftsmanship being displayed. Some of the relevant questions for me, when it comes to craftsmanship, are:

What is the overall structure of the piece? Is it in sonata form, theme and variations, etc.?

Are there new variations/innovations within the structure? Are my expectations being subverted structurally?

How is the theme being developed? What are the changes that the composer makes to the core ideas? Do they speed up, slow down, change key, add/subtract notes?

Does the music continue to surprise me? Does it go somewhere, or does it stay too long in one place?

Having said everything I've just said about these quotes overstating the claim on Bach, I will now potentially look like a hypocrite, because I think Bach is fully deserving of being called Bach der Einzige (the one and only). His craft is the best I've ever listened to.

There are so many examples of this that come from Bach that it's hard to know which one to choose, but I cannot go wrong with The Art of Fugue. This recording is, to my mind, the best.

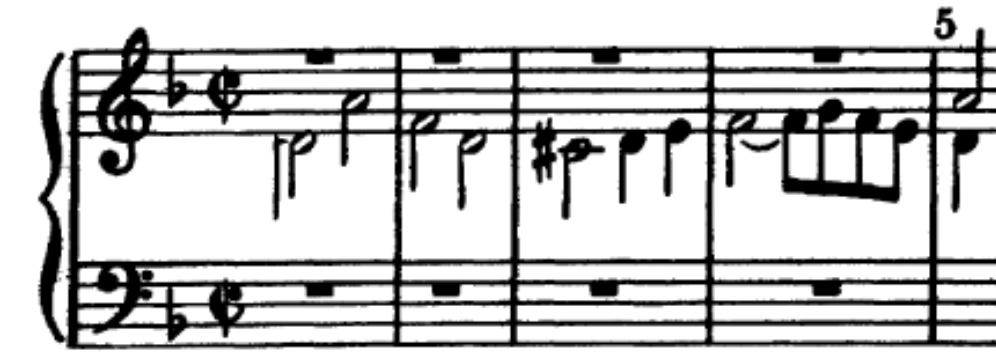

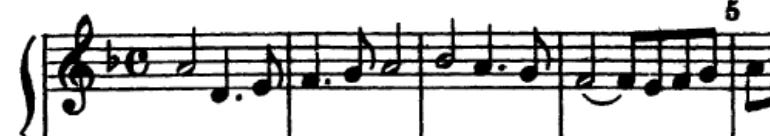

An unfinished work from the end of Bach's life, it consists of 14 fugues, 4 canons, and a mirror fugue for two keyboards. Roughly, a fugue is a piece where there are separate lines that occur and reoccur at different registers. These lines are called the "voices", and often you can split them into the standard soprano, alto, tenor, bass. We aren't going to look at the canons today, as I myself do not really understand them yet. The entire work, which is well over an hour long, is based on the development of these four measures:

This is the first four measures of the first fugue. Once again, that is the center of the entire work. Bach is going to make well over an hour, and 80 pages worth, of music (which was still unfinished!) out of these four measures. Of course, that doesn't mean he uses no other ideas, but most of his primary thematic material is built from variations on these four bars. We see this immediately, in the next four bars of the fugue:

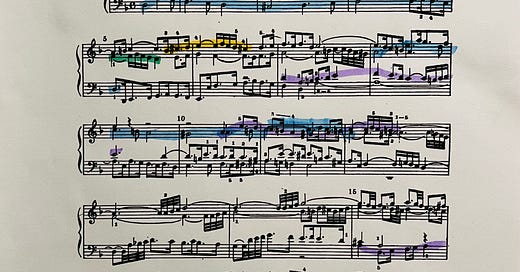

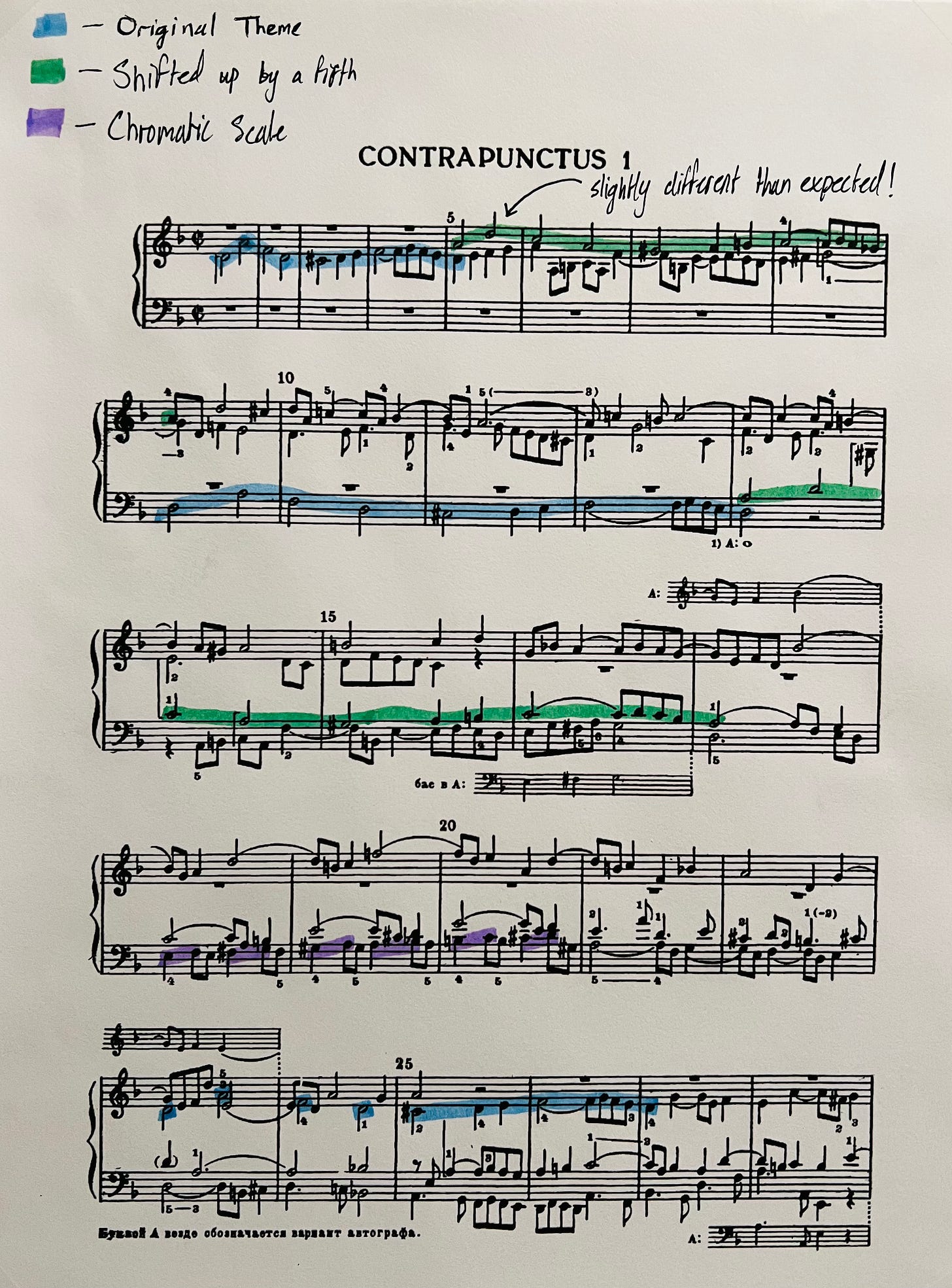

The top line is a shift of the original theme, upward a fifth, with one small exception – the second note is shifted down a whole step, to keep our tonal center firmly in the land of D Minor. The original line goes off and does its own thing beneath the new, higher version of the theme. If we track this for the whole first page, we get something like this:

I've also added a little purple for a chromatic scale I noticed, hidden amongst the left hand crawling upwards. I'm sure you could find more things like this if I stared at the page for long enough. All in all, this is pretty standard, dare I say basic, technique for Bach. Truly, understand that this is nothing for Bach, although it would make certain unnamed modern artists’ heads spin. Let's now turn, quickly, to the Contrapunctus V.

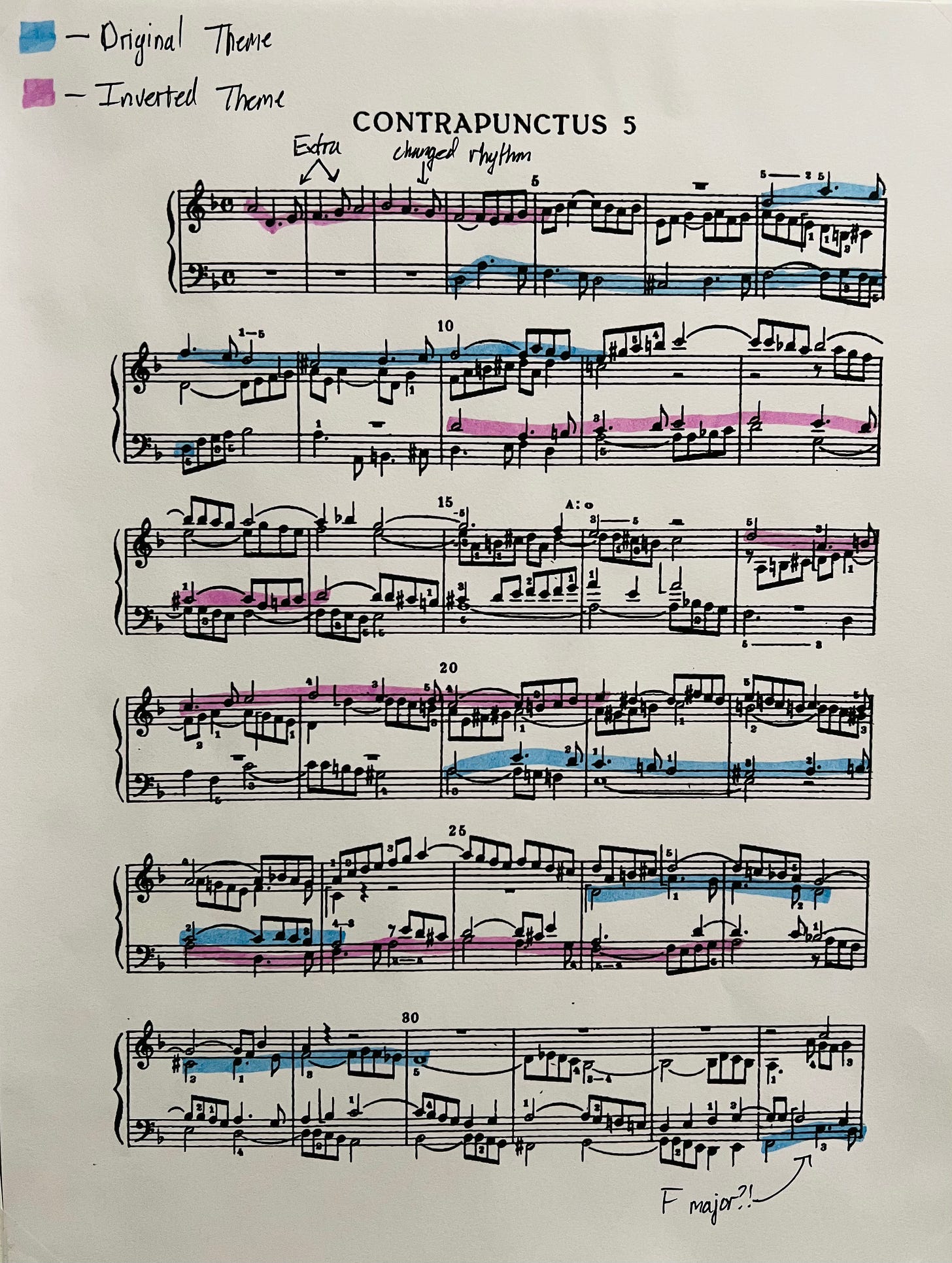

Here, instead of directly shifting the theme upwards, Bach inverts the theme; he flips the notes "upside-down":

A math major such as myself might say that he reflected the notes, in this case across the lower treble clef F. This is, for us, the first time we've seen this idea, but Bach actually introduced it back in Contrapunctus III. He's also added some 8th notes in between the original notes of the theme, which function as "bridges" between the notes, as well as slightly changing the rhythm at the end of the line. If we do a similar exercise on the first page as we did in Contrapunctus I, we get this:

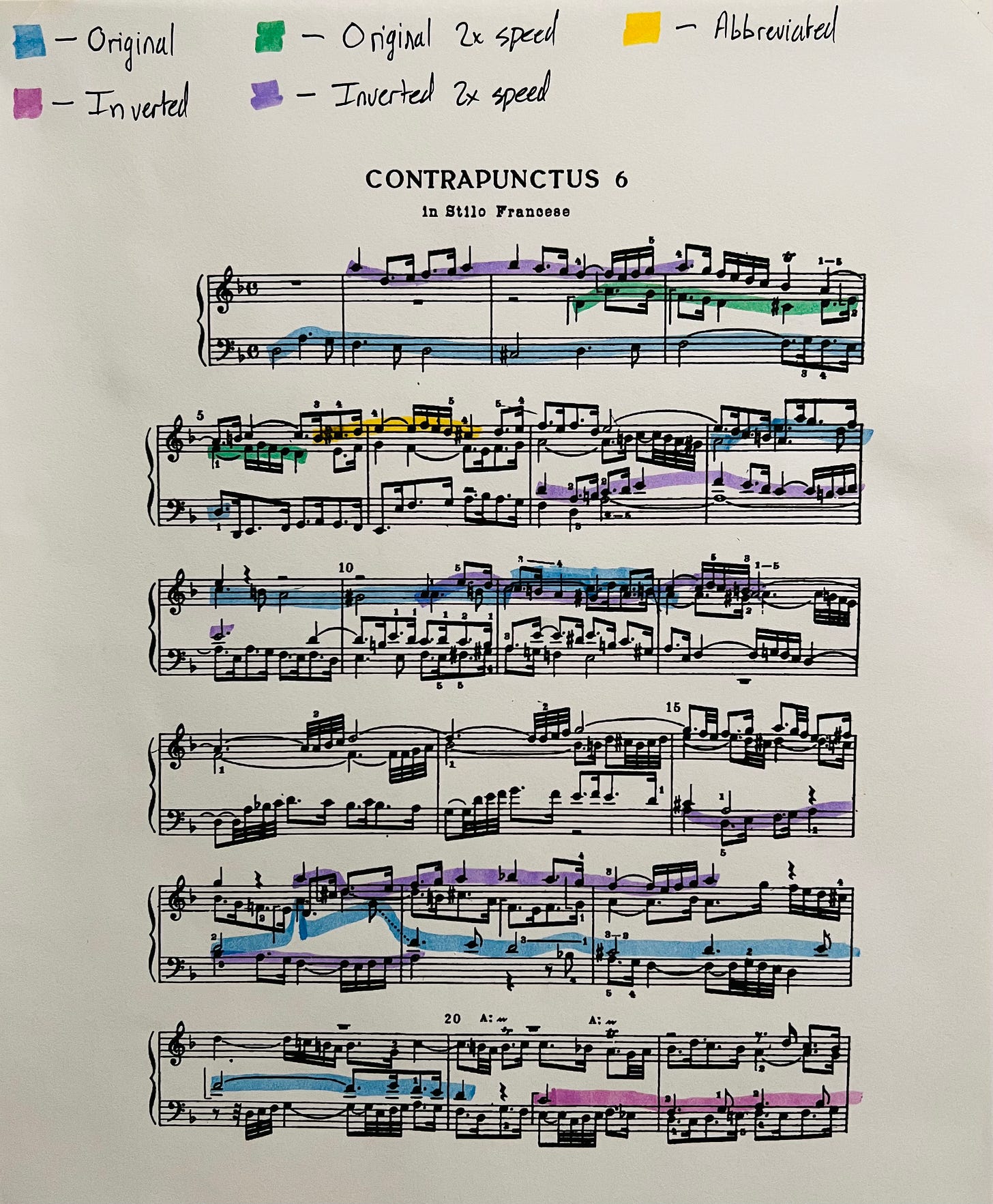

Note the seemingly odd change to F Major at the bottom of the page; Bach has modulated into the Major Third of the key, which is the relative major for D Minor. You might think that this is already impressive, but we have not yet seen the final example I want to look at; the first page of Contrapunctus VI.

This is where Bach really starts to show off. He takes his theme from the 5th fugue, with its inversion, and often speeds them up to twice their original speed:

So, now we have four things to keep track of; the theme, its inversion, and both of their sped-up analogues. Once again doing our highlighting on the first page alone, we get this:

Just for kicks, I guess, Bach throws in a little abbreviated version of the theme, which I marked in yellow. As you can see, there is so much craft going on here, and I have barely scratched the surface. When I spotted that third line, where he interweaves the original theme with its inverted, sped-up version, which are to both be played with the right hand…my brain nearly exploded. And yet, we've only looked at three of the eighty pages there are in this work! I'm sure a music theorist could tell me way more than I can see currently; there's depths to be plumbed about the harmony, the lines that come after the introduction of the themes, and so much more. There is no doubt in my mind – I will never fully understand this work.

As I mentioned at the beginning, I do not listen exclusively to classical; I have now found artists in most genres that I can truthfully say I enjoy and appreciate listening to. To my mind, though, classical music in all its forms cannot be topped, for the reasons I've laid out here and for many others. The sorts of analysis, of emotivic vitality, of God-given craft, that can be performed and heard and seen in the likes of Bach, Rachmaninoff, Mozart, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Medtner...the list is far longer than we have time for today. (And if there's an artist or artists, classical or otherwise, who strike you in the ways Bach and Rachmaninoff strike me, please put a comment below!) Music, to me, is about the interplay between these two axes of craftsmanship and storytelling, and that is ultimately what I am searching for in music. Are we not all searching for not just the best stories, but the best-told stories?

One example, to my mind, of a classical work with an extremely clear storyline is Mahler’s Sixth Symphony; in particular, the last movement feels like the tragic story of a hero.

Opus is latin for “work”, and it is standard nowadays for people to catalog the pieces of a composer by its opus number – generally ordered by when it was first released. Rachmaninoff’s total compositions are not a large set. While some of his pieces (e.g., his songs for solo piano and voice) are not given opus numbers, the last opus number is still only Opus 45, making the Etudes-Tableaux a relatively late composition.

I am musically uneducated, and probably uncouth. Nonetheless, my favourite piece is Chopin’s Opus 10 No. 3 etude.

To continue the Douglas Adam’s motif, I think Bach belongs as number 42 on any list of composers.

I’m a late comer to classical music but it is definitely what I listen to the most as I’ve gotten older.