In my efforts to rekindle the flames of friendship in our culture, I have discovered that history is stranger and more beautiful than fiction. The pre-modern world is culturally divergent from ours in many ways. Jesus, far from being the stalwart defender of the “nuclear family" that so many imagine, neutered the strength of bloodline-relationship in favor of spiritual relationship and removed the force of hierarchy amongst his followers. Paul, furthering and expanding upon Jesus's teachings, viewed his epistolary recipients as siblings, the strongest emotional category their culture contained.

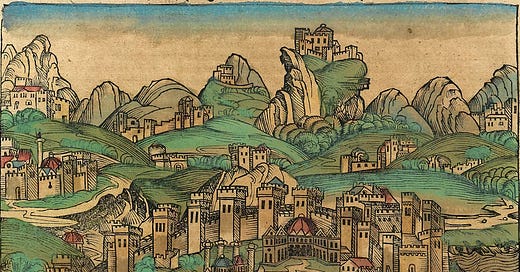

Since I am working from within a Christian framework, I am especially (though not exclusively) interested in learning how other Christian cultures have constructed views of friendship or brotherhood. It is for this reason that we leap forward in time to the Byzantines. Byzantine culture, unlike the great empires which preceded it, was one explicitly shaped by the church. Indeed, it is often difficult to separate church from politics during this era; the iconoclast controversy1 was a political struggle just as much as a theological one.2 Emperors alternated between iconoclast and iconophile. Church leadership often sought to make the next emperor one who would align with their own views. Even the laypeople were invested in the arcane theological debates of their age. It is no surprise, then, that Byzantine relationships also have a particularly Christian character.

Byzantine culture, much like the Ancient Near East, was one of honor and shame. Such a society views loyalty as a "precious commodity",3 primarily because survival depended on support from one's kin group. As such, people were incentivized to find ways to solidify support from other people, in particular by extending the kinship relations to them. Those considered family were expected to support one another at the expense of nearly everything else, including their own personal happiness. If one could claim the rights of family with another, one had an ironclad promise of loyalty.

In America, we have one primary way of extending kinship relations—marriage. When two people are married, their families are tied together by extension. Secondarily, adoption is a form of relationship that recognizably extends family ties, but it is rare; certainly not on the scale and popularity of marriage.

Things were done differently in Byzantium. Marriage was, unsurprisingly, a primary method of extending kin groups. But there were three further forms of created kinship: adoption, godparent-hood, and brother-making.

Byzantine Marriage

Byzantine marriage was both socially and legally recognized; husband and wife were expected to cohabitate and bear children. The legal tradition has its roots in the precepts of Roman law. Somewhat surprisingly, the ecclesiastical rituals for engagement and marriage did not acquire legal force until the 9th century. Before that point, a blessing from a priest was optional.4

Unlike American marriages, Byzantine marriages were arranged by the (male) heads of household. Often, marriages were the subject of "negotiations"5 between families over things like the dowry and, less commonly, the bride price. This was especially pronounced in the aristocratic ranks; when large amounts of property were at stake, marriage was a prime weapon for political maneuvering. The Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) was the offspring of two prominent families, and his five daughters were all married to different scions of political powerhouses.6

One unique point of legal code regarding Byzantine marriage is their laws against incest. Descending from Roman law, marriage with a member of one's family was strictly prohibited—in this case, to the seventh degree of consanguinity. Further, the Byzantine interpretation of consanguinity was to simply count the number of generations back until one finds a common ancestor. This meant that anyone within sixth cousins was not allowed to marry, which meant that "Byzantine legal experts were frequently consulted in unclear cases."7 Marriage also affected consanguinity for ascendants; for example, the wife's uncle could no longer marry the husband's niece.

Byzantine Adoption

Adoption was another standard practice, once again inherited from the Roman custom. Most adoptions were driven by the desire to find an heir. Just like marriage, adoption had legal force before acquiring ecclesiastical force—it also gained an associated church ceremony during the early 9th century.

It is unclear how common adoption was in Byzantium. We know that it was not wholly arcane: Emperor Leo VI's legislation "explicitly allowed childless women and eunuchs to adopt."8 It appears to have been particularly common in the Byzantine high society, as another political tool in the toolbag. Emperor Michael III adopted the man who would eventually succeed him on the throne, Basil I.

Byzantine Godparenthood

Godparenthood, in the Greek synteknia, lit. "together with child" (that is, co-parenthood) was another important way to extend the Byzantine family boundary. Claudia Rapp writes that the godfather and biological father "were expected to remain in close contact also at other times and to lend each other mutual loyalty and support."9 The godparent had responsibility for the child's Christian upbringing—a uniquely Christian innovation.

Godparents were given standing invitations to family feasts. These were a sign and seal of trust, as family feasts were one of the few events where people could access female family members who were otherwise sheltered. The godfather was also the best man when his godson married. In general, a relation of godfatherhood allowed the blood-father and godfather to move freely between their two households.

To further explain how seriously the Byzantines took synteknia, I should also note that godfatherhood entailed the same legal restrictions upon marriage as marriage did. So, within Byzantine society, not only could you not marry a sixth cousin, but you could not even marry the sixth cousins of your godparent. Why? Rapp writes the following:

On the grounds that the spiritual relationship created at baptism is at least as strong as a blood relationship, synteknia carried the same incest prohibitions as marriage and affected the choice of marriage partners for the descendants.10

This relationship carried with it almost all of the same social and legal benefits as marriage. The only domain where it lacked was economically; co-parenthood did not change the distribution of wealth or inheritance of property.11

Byzantine Brother-making

Lastly—and for my project, most importantly—we turn to brother-making, or adelphopoiesis. To the shock, surprise, and stupefaction of all, Rapp's book Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium is focused on this particular ritual. This ritual was cast into relative prominence with the bombshell book (insofar as an academic work of history can be a bombshell, anyway) Same-Sex Unions in Pre-modern Europe, by John Boswell. Boswell, who was a Yale historian and a gay Catholic, claimed that adelphopoiesis was a form of church sanctioned same-sex union with sexual overtones. As you can imagine, since this book was published in 1994, near the apex of the AIDS crisis, it caused a firestorm in both evangelical and academic circles.

Before we can dive into adelphopoiesis, which will be a several-part series in the coming weeks and months, we need to set some background. Because adelphopoiesis is such a unique cultural phenomenon, it will be helpful to get a sense of the lay of the conceptual landscape that the Byzantines were working within.

In late antiquity, brotherhood terms were "ubiquitous and often vague"12 because they were often used to claim equality with someone, real or imagined. Equality between brothers was assumed, so many groups formed around a common trade would use this language, albeit not in Byzantine trade associations. (See my previous articles here and here for more on this tendency in the ANE.) It was used, however, between high-ranking Byzantine clergymen and occasionally in the military.

There is some evidence of religious groups outside the high church using brotherhood language as well. Most of it comes from groups of the poor coming together to collectively pay for one another's burial, something they could not otherwise afford.

Legal brotherhood existed outside Byzantium, especially in Spain, southern France, and Italy. These relationships, called affrèrements, were primarily utilitarian and contractual by nature, recognized by the state without a church blessing. They existed during the 11th through 18th centuries, being the most prominent from the 14th century onwards. Although these were mostly concerned with the sharing of property rights, and therefore between two married men, they did also contain expressions of affection, and sometimes two unmarried men would enter into one of these contracts.13

Orthogonal to legal brotherhood and adelphopoiesis were the so-called "sworn brotherhoods," either called phratria or synômosiai. These were never seen in a positive light in Byzantium because they were most often groups of young men who swore to do anything to gain power, including violence. Although the word synômosia was originally defined neutrally as "friendship accompanied by oaths", by the 13th century it was defined as "plotting against others".14 This is not least because so many of these groups were involved in the overthrowing of emperors.

An important question is how strongly Byzantine views on friendship were informed by those of the ancients. The saying that friends are "one soul in two bodies" goes back to Aristotle and was commonplace among the ancients. Unsurprisingly, it is frequently referenced in the rituals for adelphopoiesis.

Plutarch may be taken as representative of the ancient views; see his essays De Amicorum Multitudine and De Fraterno Amore. Many Christians in Late Antiquity stressed having a lifelong close friend to act as a mirror for oneself. However, the Christian concept of caritas, charity, eventually crowded out the preceding notions of amicitia and philia. While the West continued to think about the notions of amicitia, the East vastly preferred kinship language over friendship. Friendship was seen as a gateway to deeper things, like synteknia and, as we shall see, adelphopoiesis.

Part of my excitement over this topic is because almost everything it touches appears to have direct application to our society today. I've written a little bit on the need I see for friendship to return to prominence in our society (see Relational Itinerancy and Knowledge and the Body), but I haven't explained the full scope of what is brewing.

I am increasingly convinced that our society is relationally broken, and that so much of our struggles in life are because we don't understand friendship. Adelphopoiesis is a window into an alternate universe—a world where friendship is recognized not only as good or valuable, but as central and essential to the human experience. It is a world where friendship is no longer a diminutive, weakened form of marriage, but a cherished archetype in its own right.

Now that we have a foundation in Byzantine culture, we will be able to more firmly discuss adelphopoiesis, its origins, and its importance in Byzantine society. These will be tackled in the rest of the series.

The iconoclast controversy was an 8th-9th century debate within the church over the use of images for the purpose of worship and veneration. It bled over into the realm of politics, several rival “ecumenical” councils were held, and culminated in the second council at Nicaea.

Incidentally, this is part of why I'm Protestant; Nicaea II is a document too influenced by political desires at the expense of historical accuracy for me to assent to its claims. But that's neither here nor there, and this is not a point I’m going to argue about on the internet; that’s just my two cents.

Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium, p. 9.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 10.

Ibid, p. 13.

Ibid, p. 11.

Ibid, p. 11, emphasis mine.

Ibid, p. 11-12.

Ibid, p. 13.

Ibid, p. 21-25.

Ibid, p. 25.